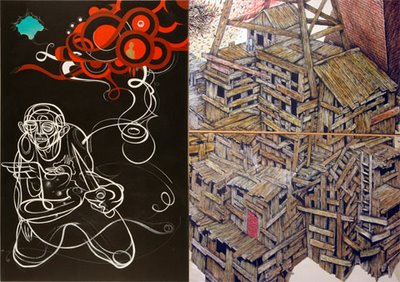

As the boundaries between urban and suburban become blurred, the city resembles more a landscape (or topography), rather than a volume. Installation art opens the possibility of exploring the limits of corporality and gregariousness.

From here on, let's look at the following: 1- Physical environment, 2- Medium in which the craftsman works, 3- Materials and techniques, personality of the artist, 4- The artist's role in society, 5- The nature of the visual language artists use, 6- The visual forms to which the artist has been exposed and 7- The nature of the aesthetic canon by which the creative process is guided and judged.-- Evelyn Payne Hatcher, Art as Culture: An Introduction to the Anthropology of Art (Bergin & Garvey, 1999).

From here on, let's look at the following: 1- Physical environment, 2- Medium in which the craftsman works, 3- Materials and techniques, personality of the artist, 4- The artist's role in society, 5- The nature of the visual language artists use, 6- The visual forms to which the artist has been exposed and 7- The nature of the aesthetic canon by which the creative process is guided and judged.-- Evelyn Payne Hatcher, Art as Culture: An Introduction to the Anthropology of Art (Bergin & Garvey, 1999).