Thursday, April 12, 2007

The Art Market

For the last few years, the media have trumpeted contemporary art as the hottest new investment. At fairs, auction houses and galleries, an influx of new buyers--many of them from the world of finance--have entered the fray. Lifted by this tidal wave of new money, the number of thriving artists, galleries and consultants has rocketed upwards. Yet amid all this transformative change, one element has held stable: the art market's murky modus operandi. In my experience, people coming from the finance world into the art market tend to be shocked by the level of opacity and murkiness," says collector Greg Allen, a former financier who co-chairs MoMA's Junior Associates board. "Of course, there's a lot of hubris--these people made fortunes cracking the market's code, so they tend to think the opacity is someone else's problems. But the mechanisms are not in place to eliminate ethical lapses or price-gouging, and the new breed of collectors is definitely more likely to pursue legal options. And once things go to court, a lot of the opacity gets shaken out." The art trade is the last major unregulated market," points out Manhattan attorney Peter R. Stern, whose work frequently involves art-market cases. "And while it always involved large sums of money, there was never the level of trading and investing that we have now. I'm increasingly approached by collectors who have encountered problems." Stern represented collector Jean-Pierre Lehmann in his winning case against the Project Gallery, which captivated the art world by revealing precisely what prices and discounts Project Gallery Chief Christian Haye had offered various collectors and galleries on paintings by Julie Mehretu--information normally concealed by an art world omerta. --Time To Reform The Art Market? by Marc Spiegler for The Art Newspaper, 2006.

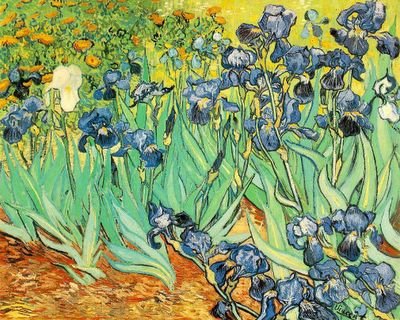

Highest bid. “The sale in 1987, at auction by Sotheby's, of van Gogh’s Irises for $53.9 million was the highest ever price paid for a painting. It now turns out that half the price--$27 million--was loaned the “buyer” by Sotheby's which has retained possession of the painting for all but six months since the sale and has it now. The sale, if that is what it was, has the art world in an uproar. It raises the troubling question: Was this just a way to kite prices? The tab on old and new masters generally tends to rise when a benchmark purchase of this magnitude and notoriety is made; whatever Sotheby ultimately nets on “Irises,” the value of the remainder of its vast inventory is increased. As Alan E. Salz, Director of Didier Aaron gallery puts it, “Every painting sold since then has been measured against it...[and] ...maybe that wasn't a real price.” The art world is disturbed about more than the fact that this particular sale may have been manipulated: David Tunick, a New York dealer says “the art market has become so monetized...people have begun to think of art as a legitimate form of investment.” Richard L. Feigen, another art dealer notes “It's exactly like buying on margin ... by extending credit you are further inflating the prices, which are rapidly getting out of control.”-- Murray L. Bob; Monthly Review, Vol. 41, March 1990.

Art auctions. In an art auction, participants bid openly against one another, with each bid being higher than the previous bid. The auction ends when no participant is willing to bid further, or when a pre-determined "buy-out" price is reached, at which point the highest bidder pays the price. The seller may set a 'reserve' price and if the auction fails to have a bid equal to or higher than the reserve, the item remains unsold. "Art prices were relatively stable between the two world wars, but they began to rise in the 1950s. Prices for Pablo Picasso's works were thirtyseven times higher in 1969 than in 1951, and prices for Marc Chagall's works rose fiftyfold over that period (Myers, 1983). The increase in the price of art was especially dramatic after 1983, with prices peaking between 1987 and 1990 and then falling somewhat after 1990. Picasso's Yo Picasso sold at auction in 1989 for $47.9 million, twice the pre-auction estimate and eight times what it sold for in 1981. Jasper Johns' False Start sold in 1960 for $3,150; in 1988, it brought $17.5 million at auction. From 1975 until the late 1 980s, works by the following artists recorded these price increases: Jackson Pollock, 750 percent; Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 490 percent; Claude Monet, 440 percent; Edgar Degas, 350 percent; Camille Pissarro, 220 percent; and Alfred Sisley, 220 percent ( Duthy, 1988a, 1989b). Even works by more obscure painters have skyrocketed: from 1975 to 1988, prices for watercolors by English artist Thomas Girtin increased by 310 percent, prices for paintings by Swedish artist Bruno Liljefors rose by 340 percent, and prices for works by Scotland's J. D. Fergusson appreciated by 460 percent."-- Art Crime, by John E. Conklin; Praeger Publishers, 1994.

The art museum. An exhibition provides the objects and information necessary for learning to occur. Exhibitions fulfill, in part, the museum institutional mission by exposing collections to view, thus affirming the public’s trust in the institution as caretaker of the societal record. Museum exhibitions also accomplish several other goals. These include: Promoting community interest in the museum by offering alternative leisure activities where individuals or groups may find worthwhile experiences. Supporting the institution financially: exhibitions help the museum as a whole justify its existence and its expectation for continued support. Donors, both public and private, are more likely to give to a museum with an active and popular exhibition schedule. Providing proof of responsible handling of collections if a donor wishes to give objects. Properly presented exhibitions confirm public trust in the museum as a place for conservation and careful preservation. Potential donors of objects or collections will be much more inclined to place their treasures in institutions that will care for the objects properly, and will present those objects for public good in a thoughtful and informative manner.-- Museum Exhibition: Theory and Practice, David Dean; Routledge, 1996

Contemporary art gallery. A generally a for-profit, privately owned businesses that sells artworks. There are also galleries run by art collectives, not-for-profit organizations, and local or national governments. Galleries run by artists are sometimes known as Artist Run Initiatives, and may be temporary or otherwise different from the traditional gallery format. Galleries are distinct from art museums. Other than size, the biggest difference between a gallery and a museum seems to be that galleries sell their work, often for a profit. However there are many galleries that do not sell artwork, so there is a considerable grey area.

Many contemporary art galleries specialize in avant-garde art, and others specialize in anything from old-masters to local artists to art-objects, crafts, etc. Contemporary art galleries are often found clustered together in urban centers such as the Chelsea district of New York or Wynwood, in the old warehouse district in Miami.

Many contemporary art galleries specialize in avant-garde art, and others specialize in anything from old-masters to local artists to art-objects, crafts, etc. Contemporary art galleries are often found clustered together in urban centers such as the Chelsea district of New York or Wynwood, in the old warehouse district in Miami.

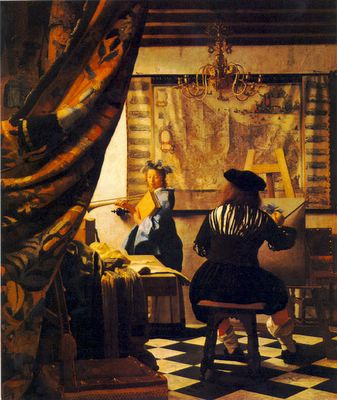

The art critic. The critic's job is not simply to evaluate what's good or bad. It would be too boring to constantly declare, "This is bad" or "This is good." [...] In addition to evaluations of good and bad, you may enjoy a critic's skillful description of an installation (what the experts call ekphrasis). Take it as a sort of movie preview, something writer Giorgio Vasari regularly did for his readers in Renaissance Florence. A writer may go "historic" like J.J. Winckelmann (the purported father of art history) and inscribe the artwork within a broad context that derives implications by analogy. Or the critic can emulate Denis Diderot's technique of moral embroideries -- the kind of thing Arthur Danto achieved in his essay on Mapplethorpe's photography. Another approach is to analyze the artist's desires and obsessions, as Thomas Mann did with Dürer's Melancholia in his novel Doctor Faustus. - Alfredo Triff, Miami Arts Explosion.

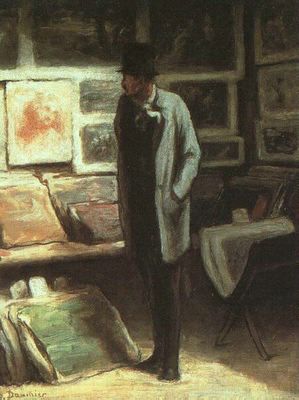

The curator. The role of the curator will encompass: collecting objects; making provision for the effective preservation, conservation, interpretation, documentation and cataloging, research and display of the collection; and to make them accessible to the public. A curator of a cultural heritage institution (i.e, a gallery, library, museum or garden) is a person who cares for the institution's collections and their associated collections catalogs. The object of a curator's concern necessarily involves tangible objects of some sort, whether it be inter alia artwork, collectibles, historic items or scientific collections. "Since the 1990's the presentation of art is more dependent on the curator than ever. The distinction between artists and curators is now blurred; curators have become more like artists. What gives biennials their emotional and intellectual pressure is the sense of curatorial mission. The candor with which many curators are willing to reveal their doubts as well as their certainties gives these spectacles some possibility of a human scale."-- Michael Brenson; Art Journal, Vol. 57, 1998.

The collectors. “My wife and I decided early on that since we made our living in the arts we would plow back all our earnings to the arts and museums and universities...[W]henever we got a few bucks ahead at the end of the year, we spent it on art. And we wanted art to represent what was being done during my lifetime -we were rather strict on that. That figures from 1907 through abstract expressionism and the flowering of New York art.” The Micheners collected very carefully. In fact, even before he bought his first painting for the collection, Michener said he “set aside a three-month period during which [he] read practically everything written on contemporary American painting, cross indexed 163 major books, essays and catalogs, and drew up a chart summarizing the opinions of critics, museum people, the general public and others.” It was a methodical passion. He was ultimately recognized by the White House Arts Program for his financial assistance to artists, assistance that is well-represented in his gift of art to The University of Texas at Austin.

The art dealer. "In 1957, when he opened his gallery in New York, Leo Castelli was nearly fifty years old. Within ten years' time he became the most interviewed, talked about, and envied member of his profession in the United States. […] By the mid-1960s the Castelli roster included a constellation of artists who were controversial enough to attract those collectors always on the lookout for promising shifts in the tides of art. Frank Stella, rebelling against Abstract Expressionism, offered large canvases painted in broad black stripes in geometrical patterns with thin lines of bare canvas showing in between. These, he insisted, should simply be looked at, not analyzed; in other words, "What you see is what you get." […] Once Pop Art entered the scene, it was inevitable that Castelli, unfailingly responsive to new and promising trends, would take it up. Three of its practitioners, Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, and James Rosenquist, entered Castelli's stable in the early 1960s. Allan Kaprow, an artist best known for the invention of "happenings," nonverbal entertainments of minimal intellectual content that appealed to enthusiasts of Pop, brought Lichtenstein and the Castelli Gallery together."-- From Landscape with Figures: A History of Art Dealing in the United States, by Malcolm Goldstein; Oxford University Press, 2000.

The artwork. 1- An artifact designed to bring about aesthetic experiences and aesthetic perceptions, or to engender aesthetic attitudes, or to engage aesthetic faculties, et cetera. The art object is something designed to provoke a certain form of response, a certain type of interaction. 2- An experience... integrated within and demarcated in the general stream of experience from other experiences. An artwork is finished in a way that is satisfactory; a problem receives its solution; a game is played through; a situation, whether that of eating a meal, playing a game of chess, carrying on a conversation, writing a book, or taking part in a political campaign, is so rounded out that its close is a consummation and not a cessation. Such an experience is a whole and carries with it its own quality and self-sufficiency.

The artist. Mark is a starving artist. He abandoned the world of material comfort, a well-stocked refrigerator, and dance lessons at the Scarsdale Jewish Community Center to live in a rat-infested East Village loft with his starving artist friends. Nowadays, using his video camera, he documents an aggressive protest against a real estate developer's plan to turn Mark's loft, along with the vacant lot next to it that is inhabited by a group of homeless people, into a high-tech cyber-arts studio. When in an unexpected twist his videos turn out to have commercial appeal, Mark faces an angst-ridden choice: Should he sell his work to a nasal-sounding executive with a cell phone and a beeper, leaving behind his self-imposed outsider status as an artist but gaining financial security and mainstream popular appeal? Or should he renounce commercial valuation of his work, forfeiting his chance for mainstream status and economic power but preserving his artistic integrity?-- Portrait of the Artist as a Young Account Executive, by Tara Zahra; The American Prospect, September 1999.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)