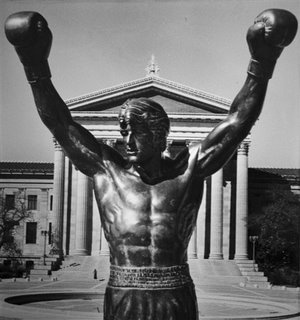

In 1982 United Artists film studios installed a statue of Rocky Balboa, played by Sylvester Stallone, at the top of the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art for the making of Rocky III. In the film, the statue is ceremoniously dedicated in front of a cheering crowd and a humbly bashful Rocky. After Rocky III, Stallone donated the film prop to the city of Philadelphia, assuming that the statue would remain in its trategically significant position, overlooking the grand Benjamin Franklin Parkway. But, after much controversy, the statue was removed to the Spectrum, the sports stadium in South Philadelphia where the fictional Rocky and the real Stallone have their roots. In 1989, United Artists requested permission to reposition the statue for the filming of Rocky V. Having been burned the first time around, when they had to pay to have the statue removed museum authorities negotiated to have the film studio remove the statue immediately after the shooting. Stallone reopened the debate regarding the proper home for the Rocky statue at a press conference that generated much interest in his new film, supposedly the last in the series. Stallone claimed that he had done as much for the museum as Walter Annenberg (who donated $5 million and recently loaned his art collection for exhibition at the museum) and that he had single-handedly done more for Philadelphia than Benjamin Franklin. Museum authorities were once again accused of elitism, and the media eagerly picked up the ball and stirred up the old controversy, casting it in the expected terms of art authorities versus ordinary citizens, elite culture versus popular culture. --Harriet F. Senie, Sally Webster, Critical Issues in Public Art (Westview Press, 1992).