Thursday, March 22, 2007

Conceptual art

1- According to conceptual art, the "concept" is more important than the work itself. This is not new (idealists have maintained that conception is more important than execution in that ideas are unpolluted by accidents): Art as a mental form; perceived, evaluated and savored as ideological and communicative instead of object-like and/or "expressive." Anything that is made up of "information" (including a written proposal, photographs, documents, maps and whatnot) counts as conceptual (the term has come to encompass all art forms outside traditional painting or sculpture). 2- Conceptual art can be traced back to Marcel Duchamp, who from the second decade of the 20th century produced various iconoclastic pieces in which he questioned the traditional values of the art world. However, conceptual art did not acquire a name or become a recognized movement until the late 1960s. Since then, the conceptual trend became widespread, flourishing at the same time as other movements, such as Arte Povera, Land art, Performance art and video art. 3- Conceptual art was initially anti-commercial. Artists thought that by eliminating objecthood, they would rid themselves of the problem of commodification behind “collectable art” (it didn't happen, after the movement was legitimized, conceptual art was very much collected). 4- By conveying a "conceptual message" artists rejected the Humanist stereotype of "creator" or "talent" so prevalent in the genius culture that developed since the mid-19th Century. 5- Conceptual art takes a great variety of forms, such as diagrams, photographs, video tapes, sets of instructions, and so on. 6- The movement was the forerunner for installation, digital, and other art forms in the 1990's.

Yoko Ono's "Play By Trust" (1966-86). In this installation, all the chess pieces (as well as the chessboard) are painted white. What's the idea?

Joseph Beuys' "Rhein Water Polluted" (1981). One of the many roles Joseph Beuys assigned himself was that of healer, and he often spoke of a "vast social wound that needs repair." No doubt he was making a general statement about the state of Western culture. His art offered both poetic representations of the injury and practical prescriptions for a cure, and alludes to healing techniques of all kinds, both physical and spiritual.

Chris Burden's "110" (1971). Burden's work is about the limits of the body and violence. He's best known for his 1972 "Shoot," where a friend shot him with a .22 caliber rifle. In 110, Burden lays strapped to the concrete floor, next to two buckets of water containing live 100-volt wires.

Dennis Oppenheim's "Reading Position For a Second Degree Burn" (1970). For this "piece" Oppenheim lay in the sun for five hours bare-chested except for an open book on his chest. He described the piece as having its roots in a notion of colour change. I allowed myself to be painted, my skin became pigment.

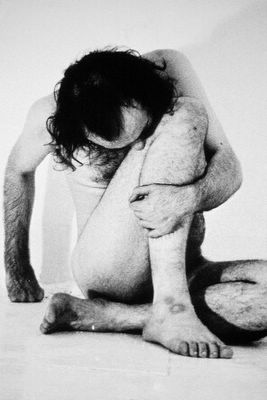

Vito Acconci's "Trademarks" (1970). Whilst sitting in front of a camera Acconci performed a series of contorted poses and bit into his arms, legs and shoulders, resulting in impressions of his teeth left on his skin. He then covered these marks with printers ink and used them to stamp various surfaces, illustrating the bodies attack on itself while also criticizing the social institutions of art and the economy, by referring to the commercial practice of branding (marking) a product for the purpose of exchange (trade).Trademarks was not carried out in front of a live audience. Instead photos where reproduced for the fall 1972 issue of Avalanche magazine, which included a text written by Acconci and a series of photos of the performance. Photo-documentation is an element that one cannot overlook for it changes the experience of the viewer entirely. Additionally, it is an element that creates even more masochistic contracts. The photographs of the artists bitten body engages the viewer's sense of touch and draws the viewer closer to the artist's body while also demonstrating the impossibility of such closeness through the presence of the photographs skin. Hence conflicting sensations of present and past, closeness and distance, attachment and alienation are felt. Although there is this distance, the viewer feels like the masochistic accomplice for without the viewers gaze the piece remains incomplete.

John Baldessari's "What Is Painting?" (mid 1960's). Baldessari's "word paintings" were very influential. In 1966, the then-35-year-old artist, who had lived in the National City section of San Diego all of his life, remained there for only three more years. This curious, unprecedented body of work proved his ticket to wider recognition. Baldessari had a knack for finding texts both cliche-ridden and strange enough to disarm the viewer.

Joseph Kosuth's "One and Three Chairs" (1965). In this piece, Kosuth displays a photograph of a chair, an actual chair, and a dictionary definition of the word "chair." The piece distinguishes between the three aspects involved in the perception of a work of art: the visual representation of a thing (the photograph of the chair), its real referent (the actual chair), and its intellectual concept (the dictionary definition). Reality, image, and concept: the three "sides" of a perceived thing.

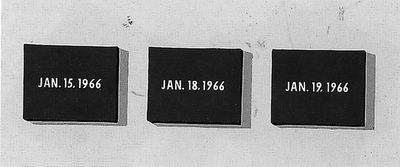

On Kawara's "Date Paintings" (1966). "Each of On Kawara's "date paintings" was completed on the date shown, the painting's sole image. Collectively they're called Todays, and the artist has made over 3,000 since the 1960s. Should he fail to finish a painting by the stroke of midnight, he destroys it. You imagine his failures to make the deadline -an unexpected visitor, the artist was struck down with sudden toothache... time ran out. "-- Adrian Searle (in a review for The Guardian, 2003)

Hans Haacke's "Condensation Cube" (1963). "make something which experiences, reacts to its environment, changes, is nonstable... make something which cannot perform without the assistance of its environment..."-- Hans Haacke (Untitled Statement, 1966).

Piero Manzoni's "Artist's Shit" (1961). Digestion and excretion. Elimination of solid waste. Making number two. Taking a big ol' dump. Humans have taken an inordinate amount of interest in their own shit production. Even primates at the zoo are frequently seen flinging or consuming their own feces, so there's a long evolutionary tradition at work. But to what end? Manzoni’s "Artist's Shit" has some forerunners in 20th Century art (Marcel Duchamp's urinal ("Fontaine", 1917) or the Surrealists' coprolalic wits. Salvador Dalì, Georges Bataille and first of all Alfred Jarry's "Ubu Roi" (1896) had given artistic and literal dignity to the word merde. The link between anality and art, as the equation of excrements with gold, is a leitmotiv of the psychoanalytic movement (and Carl G. Jung could have been a point of reference for Manzoni). Manzoni's main innovation to this topic is a reflection on the role of the artist's body in contemporary art.

Magritte's "Ceci n'est pas une pipe" (1928). "Separation between linguistic signs and plastic elements; equivalence of resemblance and affirmation. These two principles constituted the tension in classical painting, because the second reintroduced discourse (affirmation exists only where there is speech) into an art from which the linguistic element was rigorously excluded. Hence the fact that classical painting spoke – and spoke constantly – while constituting itself entirely outside language; hence the fact that it rested silently in a discursive space; hence the fact that it provided, beneath itself, a kind of common ground where it could restore the bonds of signs and the image. Magritte knits verbal signs and plastic elements together, but without referring them to a prior isotopism. He skirts the base of affirmative discourse on which resemblance calmly reposes, and he brings pure similitudes and nonaffirmative verbal statements into play within the instability of a disoriented volume and an unmapped space. A process whose formulation is in some sense given by Ceci n’est pas une pipe."-- Michel Foucault's essay from 1968, This is Not a Pipe.

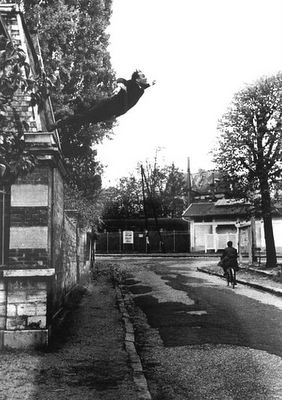

Yves Klein's "Le Seut dans le Vide" (1960). In the 1950s, France was beset by various New Waves as part of a general youth movement. Born in 1928, Yves Klein belonged to the Nouveaux Réalistes, a group of emerging young French artists. Klein’s staged leap from the second story window of his dealer Colette Allendy’s apartment in Paris inspired numerous artists to explore the body’s limits.

Marcel Duchamp's "Bicycle Wheel" (1913). "The Bicycle Wheel is my first Readymade, so much so that at first it wasn't even called a Readymade. It still had little to do with the idea of the Readymade. Rather it had more to do with the idea of chance. In a way, it was simply letting things go by themselves and having a sort of created atmosphere in a studio, an apartment where you live. Probably, to help your ideas come out of your head. To set the wheel turning was very soothing, very comforting, a sort of opening of avenues on other things than material life of every day. I liked the idea of having a bicycle wheel in my studio. I enjoyed looking at it, just as I enjoyed looking at the flames dancing in a fireplace. It was like having a fireplace in my studio, the movement of the wheel reminded me of the movement of flames."-- Marcel Duchamp, A Propos of Readymades (1951)

Egypt's Pyramids (5000 B.C.) could be seen as a series of conceptual pieces (installations in the dessert?). In his Introduction to Aesthetics, G. F. Hegel compares the pyramids to the beginning of the development of the “Idea.” (For some, “All triangles have three sides” is an a priori proposition). In his 1972 “Art History,” John Baldessari uses a similar photo to imply the same idea.