Thursday, March 1, 2007

Artist as Shaman

Shamanism is not a religion but rather a "grammar of the mind." I see it as a worldview connecting art, culture, ecology and economy.- Juhna Pentikäinen (Professor of Comparative Religion, Helsinki University Museum). The central idea behind shamanism is the contact with the supernatural world by the ecstatic experience of the shaman. There are four important constituents of shamanism: (1) the ideological premise of the supernatural world and the contacts with it; (2) the shaman as an intermediary on behalf of a human group, (3) the inspiration granted him by his helping spirits; and (4) the extraordinary, ecstatic experiences of the shaman. For his rituals, the shaman uses different objects; some are natural, such as precious stones, bits of metal, teeth and claws of animals, bones, plants, and so on (“ready-mades?”). Then, there are man-made amulets (sculptures?), which include medallions, small figurines, carved knives, drums of all sizes, wheels and masks. These serve as objects for invocation, divination and healing. Since shamanism uses diagrams to establish cosmological renditions of the universe, one could think of these diagrams as aesthetic materials. My point is that in our secular societies of the West, art can be seen as a symbolic condensation of our environment, a way to depict and evaluate our milieu. Artists produce objects that have an aesthetic function for a receiving audience. Think of the parallel between the altar and the artist's studio (or the white cube for that matter) as places of art-convocation. It may be that (as sociologist Jurgen Habermas has suggested), artists have the role of "translating chaotic everydayness into ordered aesthetic symbols for public understanding."

The artist as Shaman redefines the boundaries of art and self-realization. Says Gaugin: "When I see that young aborigen going about his tasks, I wished I could make art like that, with the oblivion of just the task at hand. No reward nor profit. That's noble."-- Letter to Daniel de Monfried, Tahiti, 1892.

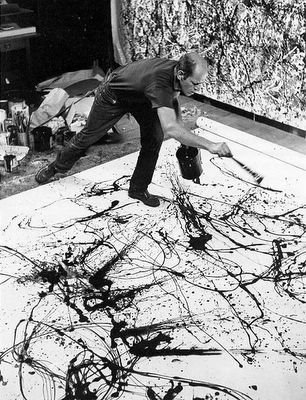

Isn't Pollock's action painting a form of "magic?" A ritual (or activity) that is thought to lead to the influencing of human or natural events by an external force beyond the ordinary human sphere, magic involves the use of special objects or the recitation of spells (words with an innate power or essence) or both by the magician. According to Friedrich Schiller (in his Aesthetic Education of Man), art can change the world. This is a more secular idea, but one that suggests a healing force. Art does precisely that.

Yoruba altar. Primitive cultures regarded certain localities (a tree, a spring, a rock) as inhabited by spirits or gods, whose intervention could be solicited by the worshiper. The altar is the place where the worshiper propitiates or pleases the gods. In a somewhat different context, can we imagine the artist’s studio a form of altar? Similarly, the studio is an intimate place for art- convocation. Gathering ideas, experimenting, realizing. There’s a unique relationship between art maker and his/her milieu; one of domain.

Neolithic altar in Malta (a predecessor of the gallery?). The white cube has an economic, social and aesthetics context within the history of Modernity. It’s a place where art is separated (perhaps alienated?) from its source for the purpose of consumption and contemplation. The art gallery elicits transactions of transcendence and economy (buying art has the resonance of a sovereign act in that the object has no other function than its contemplation). How can one rescue what is lost from the process of doing to showing?

A performance succeeds if it's believable. What does that mean? “Life is like a theater. We live and our lives take shape as if we were characters inside a play. Sometimes we’re aware of what goes on and act as if we were playing our part. It’s bizarre. We play ourselves in our script. As Nietzsche used to say, life becomes art.”—Eugene Ionesco, Fragments of a Journal (1966).

The Shaman (the artist?). I.M. Lewis explains the meaning of the word shaman among the Tungus people as “one who is excited, moved, or raised.” Vilmos Diózegi refers to the root of the term, 'sa-', as “to know.” The shaman is the one who knows. In an excited state the shaman knows more than his fellow human beings about the world of the spirits. Isn't artmaking, even art contemplation a state of (aesthetic) excitement?

Drum skin, a musical device to conjure up the spirits while mapping a social hierarchy. The most important object in shamanism, the drum symbolizes the universe (as well as countless other things). In ancient Asia the drum turned into a “wild animal” but later, with the transition to livestock raising it became a “horse.” The rhythm of the drum excites the shaman, as well as controlling the psychic state of the audience. Some shamans possess a number of costumes, drums and other accessories that are determined by the ethnical complex involved. “Without the necessary accessories the shaman could not enter the underworld.” – Mircea Eliade

Paleolithic sculptures are among humankind's first artistic creations. They are often images of animals, men, women, or priests carved in an easily manipulated stone. Each is believed to have served the function of bringing a sort of "good luck" to the creator or that person's tribal group. Ancient artists felt they were somehow affecting the physical world by making the figures. In a secular world, we've lost that motivation. Then, the Romantics (in the 19th Century) and some avant-garde movements (in the 20th Century) thought art to be a force that could educate people.

Or as mandala, separating chaos from order. A symbolic diagram used in the performance of sacred rites and as an instrument of meditation, the mandala represents the universe, a consecrated area that serves as a receptacle for the gods and as a collection point of universal forces. We humans (the microcosm) mentally "enter" the mandala toward its center (a cosmic process of disintegration and reintegration).

The origin of all aesthetic themes is found in symmetry. Before man can bring an idea, meaning, harmony into things, he must first form them symmetrically. The various parts of the whole must be balanced against one another, and arranged evenly around a center. In this fashion man's form-giving power, in contrast to the contingent and confused character of mere nature, becomes most quickly, visibly, and immediately clear. Thus, the first aesthetic step leads beyond a mere acceptance of the meaninglessness of things to a will to transform them symmetrically. -- Georg Simmel