Sunday, April 22, 2007

Job prospect

Just got an email from my editor at The Miami SunPost. They're looking for illustrators who can handle "quick, stylish drawing/computer/painting/etc." If any of you are interested, send me an email.

Tuesday, April 17, 2007

Is it art?

A few classes ago (I don’t remember) Romero Britto came up (whether his work could be called “art”). I’d like to put my ten cents: Let’s start with philosopher and art critic Arthur Danto. He suggests that we are not in a position to come up with an “a priori” definition of art (independent of the experience of artworks), because art can only be measured against the whole production of art throughout history. Some believe that art is only “one thing” and that's it (i.e., an object should not be considered “art” if it doesn’t fit such model). Say you live in 1940’s New York. The art of the moment is Abstract Expressionism (coming from prior European modern traditions in Europe). How would you have received a 1965 exhibit at MOMA entitled The Responsive Eye, showing so-called “Op Art?” If you were establishment, you’d have rejected it –as many well-known critics (Greenberg, Barbara Rose, Thomas Hess) did. Why? It didn’t fit the norms. Yet, today, Op Art is recognized as an important post-war art movement. Recently, I had a discussion with a group of people that don’t recognize performance art as a relevant art movement. How to avoid this pitfall? We know Praxiteles excelled among Athenian artists. He had remarkable craft and personal style. The reason we value his art as “canonical” is that he “fits” the tenets of Greek tradition, yet was able to push this tradition a little bit. From Praxiteles’ model, I’d like to suggest a tentative criterion for assessing “good” art: 1- Craft (meaning technical skill, proficiency of some sort), 2- Personal style (individuality that enriches and yet “fits” a given tradition), 3- The acknowledgment of peers. In a more distant place, 4- Being accepted in the historic canon. To judge a given work, one must apply the four elements together. Now, to answer the initial question: Does Romero Britto make art? Some people in the art scène would say, “Of course not.” However, Britto’s work has a personal style. His art exhibits a degree of craft (I’d say that he executes it properly). Finally, though the critics don’t accept him, he’s famous and figures in many important collectors’ collections. He has some degree of peer recognition, but his work has yet to survive the canon. Will Britto’s art become critically recognized at some point? I don’t know. We have to wait. In the meantime, is it art? Possibly. Is it good? Surely not as good as that of other Pop artists, like Warhol, Ruscha and Lichtenstein, whose influence in Britto's work is quite clear. Naïve? Decorative? It depends what you’re looking for. Sometimes, you crave a Big Mac instead of a Lobster Termidor; sometimes you want a cheap Tempranillo to down a tapa instead of a Burgundy. Now, apply that method to Britto's work.

Formalism is a typically 20th Century development. It reacts against the idea of art as representation, as expression, or as a vehicle of truth or knowledge or moral betterment or social improvement. Formalists don’t deny that art is capable of doing these things, but they believe that the true purpose of art is subverted by its being made to do these things. "Art for art's sake, not art for life's sake" is the watchword of formalism. Art is there to be enjoyed for the perception and by means of its intricate and complex form. Formalism's right hand is aestheticism, which defends that the main function of art is to produce and elicit pleasure. It informs and instruct, represent and express, but first and foremost it must please.

Many people believe that art as has a didactic function (to instill a positive influence, whether moral, social or political). Because art implants in people unconventional ideas; or breaks the molds of provincialism; or disturbs and disquiets (since it tends to emphasize individuality rather than conformity), art that does not promote a “positive” moral influence is received by the moralist with growing suspicion. For the moralist, art has the force to undermine beliefs and attitudes that are fundamental for his or her view of a good society.

The view of art as representation has been replaced by the idea of art as expression. The distinctive expressionist view of artistic creation is the product of the Romantic movement, according to which the creation of art is based on the expression of feelings. Instead of reflecting states of the external world, art is held to reflect the inner state of the artist. This, at least, seems to be implicit in the core meaning of "expression": the outer manifestation of an inner state.

It's been said that art is a means to the acquisition of truth. Art has even been called the avenue to the highest knowledge available to man (and to a kind of knowledge impossible of attainment by any other means). Knowledge in the most usual sense of that word takes the form of a proposition, knowing that so-and-so is the case. Is knowledge acquired in this same sense from acquaintance with works of art? The question is whether there is anything that can be called truth or knowledge (presumably knowledge is of truths, or true propositions) that can be found in works of art.

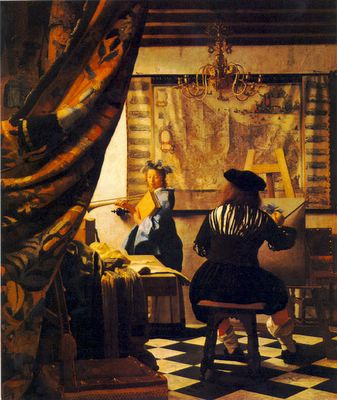

Art as imitation harks back to Plato. At some period in the history of art, people conceived art as if nature should be recorded by the artist with photographic fidelity. The invention of photography (which can do this better than any painter) could plausibly be said to have relieved the artist of any such responsibility.

For some, art should be a repository for proverbial wisdom, ancient superstitions, sentimental themes, and religious beliefs. It should accompany and celebrates what is embedded in the lives of individuals and communities: baptisms, marriages, funerals, anniversaries, sowings, reapings, and the daily routine of work. Vernacular art becomes the soul of the people.

Monday, April 16, 2007

Final Paper: D'où venons nous? Que sommes nous? Où allons nous?

1-The paper should have from 7-10 pages. No bind, arial 12 point, single spaced, stapled.

2-Three sections: Where am I coming from? Where am I? Where am I going?

3-Each section looks at a particular period in your artistic life:

a-“Where I’m coming from,” describes your background. When did art become important? What were your favorite pictorial themes (and why so)? Analyze your interests and concerns at the time. Any particular event that triggered an interest? Did you know all along?

b-“Where am I” looks at the present. Where are you with your art right now? Are you happy? Is there something that in youri opinion needs improvement? Visualize the dynamics of your style so far and comment what it means for you.

c-“Where am I going” projects yourself into the future: Use this section as a springboard to see yourself as becoming the best you can be. How do you see yourself in, say, five years from now?

4-Put all these elements in a narrative that flows. Please, don't entitle each section (the reading gets very boring); instead, suggest and imply the different stages into a consistent whole.

5- The paper should be in my mailbox at the Rainbow Building by Friday, April 27, at 2pm.

2-Three sections: Where am I coming from? Where am I? Where am I going?

3-Each section looks at a particular period in your artistic life:

a-“Where I’m coming from,” describes your background. When did art become important? What were your favorite pictorial themes (and why so)? Analyze your interests and concerns at the time. Any particular event that triggered an interest? Did you know all along?

b-“Where am I” looks at the present. Where are you with your art right now? Are you happy? Is there something that in youri opinion needs improvement? Visualize the dynamics of your style so far and comment what it means for you.

c-“Where am I going” projects yourself into the future: Use this section as a springboard to see yourself as becoming the best you can be. How do you see yourself in, say, five years from now?

4-Put all these elements in a narrative that flows. Please, don't entitle each section (the reading gets very boring); instead, suggest and imply the different stages into a consistent whole.

5- The paper should be in my mailbox at the Rainbow Building by Friday, April 27, at 2pm.

Thursday, April 12, 2007

The Art Market

For the last few years, the media have trumpeted contemporary art as the hottest new investment. At fairs, auction houses and galleries, an influx of new buyers--many of them from the world of finance--have entered the fray. Lifted by this tidal wave of new money, the number of thriving artists, galleries and consultants has rocketed upwards. Yet amid all this transformative change, one element has held stable: the art market's murky modus operandi. In my experience, people coming from the finance world into the art market tend to be shocked by the level of opacity and murkiness," says collector Greg Allen, a former financier who co-chairs MoMA's Junior Associates board. "Of course, there's a lot of hubris--these people made fortunes cracking the market's code, so they tend to think the opacity is someone else's problems. But the mechanisms are not in place to eliminate ethical lapses or price-gouging, and the new breed of collectors is definitely more likely to pursue legal options. And once things go to court, a lot of the opacity gets shaken out." The art trade is the last major unregulated market," points out Manhattan attorney Peter R. Stern, whose work frequently involves art-market cases. "And while it always involved large sums of money, there was never the level of trading and investing that we have now. I'm increasingly approached by collectors who have encountered problems." Stern represented collector Jean-Pierre Lehmann in his winning case against the Project Gallery, which captivated the art world by revealing precisely what prices and discounts Project Gallery Chief Christian Haye had offered various collectors and galleries on paintings by Julie Mehretu--information normally concealed by an art world omerta. --Time To Reform The Art Market? by Marc Spiegler for The Art Newspaper, 2006.

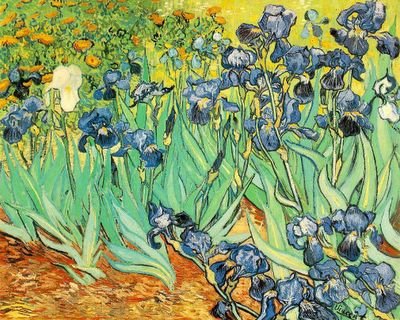

Highest bid. “The sale in 1987, at auction by Sotheby's, of van Gogh’s Irises for $53.9 million was the highest ever price paid for a painting. It now turns out that half the price--$27 million--was loaned the “buyer” by Sotheby's which has retained possession of the painting for all but six months since the sale and has it now. The sale, if that is what it was, has the art world in an uproar. It raises the troubling question: Was this just a way to kite prices? The tab on old and new masters generally tends to rise when a benchmark purchase of this magnitude and notoriety is made; whatever Sotheby ultimately nets on “Irises,” the value of the remainder of its vast inventory is increased. As Alan E. Salz, Director of Didier Aaron gallery puts it, “Every painting sold since then has been measured against it...[and] ...maybe that wasn't a real price.” The art world is disturbed about more than the fact that this particular sale may have been manipulated: David Tunick, a New York dealer says “the art market has become so monetized...people have begun to think of art as a legitimate form of investment.” Richard L. Feigen, another art dealer notes “It's exactly like buying on margin ... by extending credit you are further inflating the prices, which are rapidly getting out of control.”-- Murray L. Bob; Monthly Review, Vol. 41, March 1990.

Art auctions. In an art auction, participants bid openly against one another, with each bid being higher than the previous bid. The auction ends when no participant is willing to bid further, or when a pre-determined "buy-out" price is reached, at which point the highest bidder pays the price. The seller may set a 'reserve' price and if the auction fails to have a bid equal to or higher than the reserve, the item remains unsold. "Art prices were relatively stable between the two world wars, but they began to rise in the 1950s. Prices for Pablo Picasso's works were thirtyseven times higher in 1969 than in 1951, and prices for Marc Chagall's works rose fiftyfold over that period (Myers, 1983). The increase in the price of art was especially dramatic after 1983, with prices peaking between 1987 and 1990 and then falling somewhat after 1990. Picasso's Yo Picasso sold at auction in 1989 for $47.9 million, twice the pre-auction estimate and eight times what it sold for in 1981. Jasper Johns' False Start sold in 1960 for $3,150; in 1988, it brought $17.5 million at auction. From 1975 until the late 1 980s, works by the following artists recorded these price increases: Jackson Pollock, 750 percent; Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 490 percent; Claude Monet, 440 percent; Edgar Degas, 350 percent; Camille Pissarro, 220 percent; and Alfred Sisley, 220 percent ( Duthy, 1988a, 1989b). Even works by more obscure painters have skyrocketed: from 1975 to 1988, prices for watercolors by English artist Thomas Girtin increased by 310 percent, prices for paintings by Swedish artist Bruno Liljefors rose by 340 percent, and prices for works by Scotland's J. D. Fergusson appreciated by 460 percent."-- Art Crime, by John E. Conklin; Praeger Publishers, 1994.

The art museum. An exhibition provides the objects and information necessary for learning to occur. Exhibitions fulfill, in part, the museum institutional mission by exposing collections to view, thus affirming the public’s trust in the institution as caretaker of the societal record. Museum exhibitions also accomplish several other goals. These include: Promoting community interest in the museum by offering alternative leisure activities where individuals or groups may find worthwhile experiences. Supporting the institution financially: exhibitions help the museum as a whole justify its existence and its expectation for continued support. Donors, both public and private, are more likely to give to a museum with an active and popular exhibition schedule. Providing proof of responsible handling of collections if a donor wishes to give objects. Properly presented exhibitions confirm public trust in the museum as a place for conservation and careful preservation. Potential donors of objects or collections will be much more inclined to place their treasures in institutions that will care for the objects properly, and will present those objects for public good in a thoughtful and informative manner.-- Museum Exhibition: Theory and Practice, David Dean; Routledge, 1996

Contemporary art gallery. A generally a for-profit, privately owned businesses that sells artworks. There are also galleries run by art collectives, not-for-profit organizations, and local or national governments. Galleries run by artists are sometimes known as Artist Run Initiatives, and may be temporary or otherwise different from the traditional gallery format. Galleries are distinct from art museums. Other than size, the biggest difference between a gallery and a museum seems to be that galleries sell their work, often for a profit. However there are many galleries that do not sell artwork, so there is a considerable grey area.

Many contemporary art galleries specialize in avant-garde art, and others specialize in anything from old-masters to local artists to art-objects, crafts, etc. Contemporary art galleries are often found clustered together in urban centers such as the Chelsea district of New York or Wynwood, in the old warehouse district in Miami.

Many contemporary art galleries specialize in avant-garde art, and others specialize in anything from old-masters to local artists to art-objects, crafts, etc. Contemporary art galleries are often found clustered together in urban centers such as the Chelsea district of New York or Wynwood, in the old warehouse district in Miami.

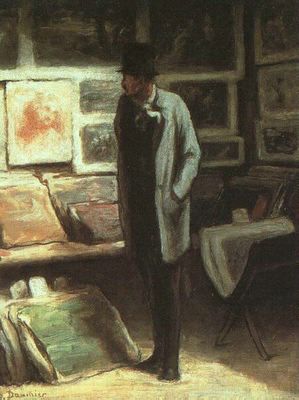

The art critic. The critic's job is not simply to evaluate what's good or bad. It would be too boring to constantly declare, "This is bad" or "This is good." [...] In addition to evaluations of good and bad, you may enjoy a critic's skillful description of an installation (what the experts call ekphrasis). Take it as a sort of movie preview, something writer Giorgio Vasari regularly did for his readers in Renaissance Florence. A writer may go "historic" like J.J. Winckelmann (the purported father of art history) and inscribe the artwork within a broad context that derives implications by analogy. Or the critic can emulate Denis Diderot's technique of moral embroideries -- the kind of thing Arthur Danto achieved in his essay on Mapplethorpe's photography. Another approach is to analyze the artist's desires and obsessions, as Thomas Mann did with Dürer's Melancholia in his novel Doctor Faustus. - Alfredo Triff, Miami Arts Explosion.

The curator. The role of the curator will encompass: collecting objects; making provision for the effective preservation, conservation, interpretation, documentation and cataloging, research and display of the collection; and to make them accessible to the public. A curator of a cultural heritage institution (i.e, a gallery, library, museum or garden) is a person who cares for the institution's collections and their associated collections catalogs. The object of a curator's concern necessarily involves tangible objects of some sort, whether it be inter alia artwork, collectibles, historic items or scientific collections. "Since the 1990's the presentation of art is more dependent on the curator than ever. The distinction between artists and curators is now blurred; curators have become more like artists. What gives biennials their emotional and intellectual pressure is the sense of curatorial mission. The candor with which many curators are willing to reveal their doubts as well as their certainties gives these spectacles some possibility of a human scale."-- Michael Brenson; Art Journal, Vol. 57, 1998.

The collectors. “My wife and I decided early on that since we made our living in the arts we would plow back all our earnings to the arts and museums and universities...[W]henever we got a few bucks ahead at the end of the year, we spent it on art. And we wanted art to represent what was being done during my lifetime -we were rather strict on that. That figures from 1907 through abstract expressionism and the flowering of New York art.” The Micheners collected very carefully. In fact, even before he bought his first painting for the collection, Michener said he “set aside a three-month period during which [he] read practically everything written on contemporary American painting, cross indexed 163 major books, essays and catalogs, and drew up a chart summarizing the opinions of critics, museum people, the general public and others.” It was a methodical passion. He was ultimately recognized by the White House Arts Program for his financial assistance to artists, assistance that is well-represented in his gift of art to The University of Texas at Austin.

The art dealer. "In 1957, when he opened his gallery in New York, Leo Castelli was nearly fifty years old. Within ten years' time he became the most interviewed, talked about, and envied member of his profession in the United States. […] By the mid-1960s the Castelli roster included a constellation of artists who were controversial enough to attract those collectors always on the lookout for promising shifts in the tides of art. Frank Stella, rebelling against Abstract Expressionism, offered large canvases painted in broad black stripes in geometrical patterns with thin lines of bare canvas showing in between. These, he insisted, should simply be looked at, not analyzed; in other words, "What you see is what you get." […] Once Pop Art entered the scene, it was inevitable that Castelli, unfailingly responsive to new and promising trends, would take it up. Three of its practitioners, Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, and James Rosenquist, entered Castelli's stable in the early 1960s. Allan Kaprow, an artist best known for the invention of "happenings," nonverbal entertainments of minimal intellectual content that appealed to enthusiasts of Pop, brought Lichtenstein and the Castelli Gallery together."-- From Landscape with Figures: A History of Art Dealing in the United States, by Malcolm Goldstein; Oxford University Press, 2000.

The artwork. 1- An artifact designed to bring about aesthetic experiences and aesthetic perceptions, or to engender aesthetic attitudes, or to engage aesthetic faculties, et cetera. The art object is something designed to provoke a certain form of response, a certain type of interaction. 2- An experience... integrated within and demarcated in the general stream of experience from other experiences. An artwork is finished in a way that is satisfactory; a problem receives its solution; a game is played through; a situation, whether that of eating a meal, playing a game of chess, carrying on a conversation, writing a book, or taking part in a political campaign, is so rounded out that its close is a consummation and not a cessation. Such an experience is a whole and carries with it its own quality and self-sufficiency.

The artist. Mark is a starving artist. He abandoned the world of material comfort, a well-stocked refrigerator, and dance lessons at the Scarsdale Jewish Community Center to live in a rat-infested East Village loft with his starving artist friends. Nowadays, using his video camera, he documents an aggressive protest against a real estate developer's plan to turn Mark's loft, along with the vacant lot next to it that is inhabited by a group of homeless people, into a high-tech cyber-arts studio. When in an unexpected twist his videos turn out to have commercial appeal, Mark faces an angst-ridden choice: Should he sell his work to a nasal-sounding executive with a cell phone and a beeper, leaving behind his self-imposed outsider status as an artist but gaining financial security and mainstream popular appeal? Or should he renounce commercial valuation of his work, forfeiting his chance for mainstream status and economic power but preserving his artistic integrity?-- Portrait of the Artist as a Young Account Executive, by Tara Zahra; The American Prospect, September 1999.

Thursday, April 5, 2007

Performance art can be a real force!

Marina Abramovic can provoke people! Want a proof? The following thread, which I've sampled for you from artblog.net (in our list of art blogs), shows how viscerally individuals can react to performance art. It all sort of begins when the blog's moderator takes a passage from my Sunpost article:

For The Lips of St. Thomas (1975), Abramovic sat at a table, eating a kilo of honey and a liter of wine, then proceeded to cut a five-point star into her stomach (with a razor blade) and whip herself until her body felt totally numb.

Franklin: Supergirl commented, I know guys in the Air Force who would do that for a dollar. Well said, my love.

As people start posting comments, there is this comment (referring to Abramovic), from an art teacher at one of our local institutions!

Opie: With all that wine and honey she didn't need a star, she needed a drain.

Or this one from a participant -whose job is described by another commenter as "snide and dismissive in tone:"

Jack: Well, you get the idea. Any connection, real or imagined, to the Abramovic stunt, I mean, performance, is purely coincidental. Far be it from me to impugn such an extravagant exhibition of pretentious, pointless posturing.

Believe it or not, they make no distinction between performance art and stunts. So, I try to explain performance art from a historic point of view:

AT: Performance art has a historic context: the civil struggles of the 1960’s in the USA and Europe, the Vietnam War, the Cold War. For these and other reasons (that we can argue some other time) the body became a locus for artistic experimentation… I don’t think that artists like Burden, Ono, de Maria, Schneeman, Beuys, Acconci, Nauman, Nitsch, Pane, Rossler, Mendieta and many more, were doing just stunts. On the contrary, I’d say that they lived at a time when the exploration (of the possibilities of the body as art) became an imperative: The body as (simultaneously) object and subject; body as transgression (the Viennese Actionists), as sex prop (Schneeman, Ono), as caricature (Nauman), as ritual (Abramovic), as political satire (Rossler), etc, etc. After Existentialism and Humanism (and the Holocaust, Hiroshima, Vietnam, and Pol Pot), all these artists explored valid questions: Is the body essential component of the self? What’s gender? What’s a female? Is the body more than representation?

This is the response I get from the same art teacher:

Opie: Justifying the elevation of such activities to the status of art by cooking up long lists of names, events and philosophies liberally spiced with current artspeak trend terms and unnamed "experts" is not intellectually responsible, no matter how many others are doing the same thing. In my opinion, anyone who buys this nonsense has lost the ability for self-determined judgement of art.

It did not matter that I produced a long list of texts by scholars on performance art (later, my comment inexplicably disappeared from the thread... coincidence?). It seems more like an empty exercise in derision and contempt, than a substantial reasoning of why they hate -or for that matter- write off performance art altogether as a legitimate art movement. I particularly single out this comment (for a person who even has the candidness of admitting she/he hasn’t seen Marina’s performance):

KQ: I haven't seen 'Lips of St.Thomas', but watching a sniper's process of executing his target 2 kilometers away with 1 shot is a performance I'd spend $$ to see...

Later, the moderator of the blog retorts:

Franklin: However, if some guy in the privacy of his home decided to carve a star in his stomach for expressive purposes, we might fairly advocate some mental health care for him.

Even after I left the thread (the discussion had already moved from the original topic to a rummaging of sorts; ad hominem platitudes, etc. Some Marc County adds:

Marc County: That's funny, I suppose, but... what argument does AT believe he is referring to? I mean, Deleuze and Guattari themselves could show up here, and I bet it STILL wouldn't amount to a real argument, any more than AT's pugnacious comments do. Seriously, these fundamentalists all sound the same to me, so sorry, it's all just more fodder for ridicule, like this... the true-believers refuse to let their dream die, truth be damned.

Frankly, I didn't know I was a fundamentalist! (which is why I have artblog.net in our page?)

The last in the thread is from (none other than a) composer of new music and a performer himself (whom I've seen, shirtless and donning a cowboy hat, riding an amplifier as if it was a horse, while making a noise piece), one whom you'd guess can understand what performance art is all about (he misses no opportunity to take a stab at our Art Issue class):

Rene Barge: Here is Pomo at its finest, perhaps those who teach “issues” can include this in the curriculum.

For The Lips of St. Thomas (1975), Abramovic sat at a table, eating a kilo of honey and a liter of wine, then proceeded to cut a five-point star into her stomach (with a razor blade) and whip herself until her body felt totally numb.

Franklin: Supergirl commented, I know guys in the Air Force who would do that for a dollar. Well said, my love.

As people start posting comments, there is this comment (referring to Abramovic), from an art teacher at one of our local institutions!

Opie: With all that wine and honey she didn't need a star, she needed a drain.

Or this one from a participant -whose job is described by another commenter as "snide and dismissive in tone:"

Jack: Well, you get the idea. Any connection, real or imagined, to the Abramovic stunt, I mean, performance, is purely coincidental. Far be it from me to impugn such an extravagant exhibition of pretentious, pointless posturing.

Believe it or not, they make no distinction between performance art and stunts. So, I try to explain performance art from a historic point of view:

AT: Performance art has a historic context: the civil struggles of the 1960’s in the USA and Europe, the Vietnam War, the Cold War. For these and other reasons (that we can argue some other time) the body became a locus for artistic experimentation… I don’t think that artists like Burden, Ono, de Maria, Schneeman, Beuys, Acconci, Nauman, Nitsch, Pane, Rossler, Mendieta and many more, were doing just stunts. On the contrary, I’d say that they lived at a time when the exploration (of the possibilities of the body as art) became an imperative: The body as (simultaneously) object and subject; body as transgression (the Viennese Actionists), as sex prop (Schneeman, Ono), as caricature (Nauman), as ritual (Abramovic), as political satire (Rossler), etc, etc. After Existentialism and Humanism (and the Holocaust, Hiroshima, Vietnam, and Pol Pot), all these artists explored valid questions: Is the body essential component of the self? What’s gender? What’s a female? Is the body more than representation?

This is the response I get from the same art teacher:

Opie: Justifying the elevation of such activities to the status of art by cooking up long lists of names, events and philosophies liberally spiced with current artspeak trend terms and unnamed "experts" is not intellectually responsible, no matter how many others are doing the same thing. In my opinion, anyone who buys this nonsense has lost the ability for self-determined judgement of art.

It did not matter that I produced a long list of texts by scholars on performance art (later, my comment inexplicably disappeared from the thread... coincidence?). It seems more like an empty exercise in derision and contempt, than a substantial reasoning of why they hate -or for that matter- write off performance art altogether as a legitimate art movement. I particularly single out this comment (for a person who even has the candidness of admitting she/he hasn’t seen Marina’s performance):

KQ: I haven't seen 'Lips of St.Thomas', but watching a sniper's process of executing his target 2 kilometers away with 1 shot is a performance I'd spend $$ to see...

Later, the moderator of the blog retorts:

Franklin: However, if some guy in the privacy of his home decided to carve a star in his stomach for expressive purposes, we might fairly advocate some mental health care for him.

Even after I left the thread (the discussion had already moved from the original topic to a rummaging of sorts; ad hominem platitudes, etc. Some Marc County adds:

Marc County: That's funny, I suppose, but... what argument does AT believe he is referring to? I mean, Deleuze and Guattari themselves could show up here, and I bet it STILL wouldn't amount to a real argument, any more than AT's pugnacious comments do. Seriously, these fundamentalists all sound the same to me, so sorry, it's all just more fodder for ridicule, like this... the true-believers refuse to let their dream die, truth be damned.

Frankly, I didn't know I was a fundamentalist! (which is why I have artblog.net in our page?)

The last in the thread is from (none other than a) composer of new music and a performer himself (whom I've seen, shirtless and donning a cowboy hat, riding an amplifier as if it was a horse, while making a noise piece), one whom you'd guess can understand what performance art is all about (he misses no opportunity to take a stab at our Art Issue class):

Rene Barge: Here is Pomo at its finest, perhaps those who teach “issues” can include this in the curriculum.

Poor guy, cannot even understand that some of the music or the art he makes has the stamp of a time and place written all over it.

My Conclusion? Performance art is a real force!

Pornography vs. Erotic art

Pornography refers to representation of erotic behavior (in books, pictures, statues, movies, etc.) intended to cause sexual excitement. The word comes from the Greek porni (prostitute) and graphein (to write). Since the term has a very specific legal and social function behind it, we must make a distinction between "pornography" and "erotica" (i.e. artworks in which the portrayal of the so-called sexually arousing material holds or aspires to artistic or historical merit). The problem is that what is considered "artistic" today, may have been yesterday's pornography. According to our definition above, there's evidence of pornography in Roman culture (in Pompeii, where erotic paintings dating from the 1st century AD cover walls sacred to bacchanalian orgies). A classic book on pornography is Ovid's Ars amatoria (Art of Love), a treatise on the art of seduction, intrigue, and sensual arousal. With Modernity, in 18th-Century Europe, a business production (designed solely to arouse sexual excitement) begins with a small underground traffic and such works became the basis of a separate publishing and bookselling business in England (a classic of this period is Fanny Hill or The Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1749) by John Cleland). At about this time erotic graphic art began to be widely produced in Paris, eventually coming to be known as "French postcards." Pornography flourished in the Victorian era despite, or perhaps because of, the prevailing taboos on sexual topics. The development of photography and later of motion pictures contributed greatly to the proliferation of pornographic materials. Since the 1960's, written pornography has been largely superseded by explicit visual representations of erotic behavior that are considered lacking in redeeming artistic or social values. Pornography has long been the target of moral and legal sanction in the belief that it may tend to deprave and corrupt minors and adults and cause the commission of sexual crimes.

William Burroughs' Naked Lunch (First Edition). Naked Lunch is considered Burroughs' seminal work, and one of the landmark publications in the history ofAmerican literature. Extremely controversial in both its subject matter and its use of often obscene language, something Burroughs recognized and intended, the book was banned in many regions of the United States, and was one of the last American books to actually be put on trial for obscenity. The book was banned by Boston courts in 1962 due to obscenity (notably child murder in pedophilic acts), but that decision was reversed in a landmark 1966 opinion by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. Naked Mr. America burning frantic with self-bone love screams out: "My asshole confounds the Louvre!... My cock spurt soft diamonds in the morning sunlight!" He plummets from the eyeless lighthouse, kissing and jacking off in the face of the black mirror, glides oblique down with cryptic condoms and mosaic of a thousand newspapers through a drowned city of red brick to settle in black mud with tin cans and beer bottles, gangsters in concrete, pistols pounded flat and meaningless to avoid short-term inspection of prurient ballistic experts. He waits the slow striptease of erosion with fossil loins.-- W.B.

Tom of Finland's Untitled (c. 1986). Pornography was, then, a category of material created, invented, and produced as a means to regulate and target the moral behavior of certain populations. The seizure of and legislation against so-called pornographic work provided a means of increasing the surveillance of working-class people and all women. For pornography to exist, "a public which might be corrupted by obscene publications had to exist." —Michel Foucault, History of Sexuality.

Jean Cocteau's erotic drawings for Le Livre Blanc (1930's). Cocteau produced eighteen explicit drawings in 1930 for the anonymously published erotic story Le livre blanc (the first edition appeared in 1928, copyrighted by Maurice Sachs and Jacques Bonjean in Paris). Pascal Pia, the author of a bibliography of the erotic collection of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, wrote that the editors received the book without its creator’s name or address and concluded that the book was published by Cocteau himself. True; the poet may have written Le livre blanc in 1927 in Chablis, where he was staying with Jean Desbordes. Cocteau's drawings have been described as "obscenely pious." They are established by quick, flowing lines, partially erotic and often sultry, featuring classical elements such as busts and centaurs. Erotic images were popular articles in France, where they were sold under the counter; people were extra careful about homosexual erotica. Cocteau described his first sexual experiences in Le livre blanc: his excitement upon seeing a naked peasant boy on horseback and two naked young gypsies on his father's estate. He also wrote about his father, in whom he recognized a homosexual inclination. Some scenes in Le livre blanc refer to Cocteau's love for Desbordes, others to the adventures of Maurice Sachs. Neither man was to survive World War II: Desbordes was tortured to death by the Gestapo, while Maurice Sachs played an enigmatic double role during the war, and subsequently disappeared.

In On Pornography: Literature, Sexuality, and Obscenity Law (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993), Ian Hunter, David Saunders, and Dugald Williamson argue, after Foucault, that pornography is not produced by the repression of true, real, or healthy sexuality. Rather it is a sexual practice produced within the context of what they call "a perpetually shifting and multiple pornographic field." The divide between aesthetics and pornography is the effect of a complex set of overlapping disciplinary apparatuses: the law, the police, literary standards, and so forth (the "pornographic field")—whose form and content necessarily changes over time. Although the unspeakable pleasure or subversive power associated with pornography paradoxically extends the tentacles of regulatory power, the boundary between the aesthetic and the pornographic also marks what Abigail Solomon-Godeau refers to as "the failure of a discursive cordon sanitaire" the attempt at segregating the licit from the illicit that constantly fails.

"For men the right to abuse women is elemental, the first principle, with no beginning . . . and with no end plausibly in sight. . . . pornography is the holy corpus of men who would rather die than change. Dachau brought into the bedroom and celebrated. . . . pornography reveals that male pleasure is inextricably tied to victimizing, hurting, exploiting; that sexual fun and sexual passion in the privacy of the male imagination are inseparable from the brutality of male history."-- Andrea Dworkin, Pornography: Men Possessing Women.

"For men the right to abuse women is elemental, the first principle, with no beginning . . . and with no end plausibly in sight. . . . pornography is the holy corpus of men who would rather die than change. Dachau brought into the bedroom and celebrated. . . . pornography reveals that male pleasure is inextricably tied to victimizing, hurting, exploiting; that sexual fun and sexual passion in the privacy of the male imagination are inseparable from the brutality of male history."-- Andrea Dworkin, Pornography: Men Possessing Women.

Sam Peckinpah's Straw Dogs (1971). "Straw Dogs was wildly controversial on its release and has remained so to this day. Most of the controversy revolved around the long and highly explicit rape scene which is the centerpiece of the film. Critics, especially feminist critics, accused Peckinpah of glamorizing rape and engaging in misogynistic sadism. They were particularly disturbed by the seeming ambiguity of the rape scene, in which Amy appears at certain points to be asking for and enjoying the abuse she is subjected to. Peckinpah's defenders claimed that the scene was unambiguously horrifying and that Amy's trauma was truthfully portrayed in the film. Peckinpah's detractors continue to cite this scene as proof of Peckinpah's chauvinism and misogyny. "-- Wikipedia, "Straw Dogs" entry.

Russ Meyer is best known as the director of "exploitation films," i.e. instead of Hollywood's traditional adherence to narrative, exploitation films include descriptive passages of violence, sexual intercourse, and other activities considered taboo by mainstream cinema. In the case of Beyond the Valley of Dolls, there was Fox's financial situation during the late 1960s, and Meyer's reputation among film critics, which influenced Fox executives to collaborate in the film's production. The result was Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, a hybrid of exploitation and Hollywood modes of production and narration.

What's "obscene?"

If something is obscene, we must understand why it is so. These are some of the five most important criteria used in America before today's Miller Test (the paragraph that follows is taken from the Wikipedia): 1- The Hicklin Test: The effect of isolated passages upon the most susceptible persons. (British common law, cited in Regina v. Hicklin, (1868) -- Overturned when Michigan tried to outlaw all printed matter that would 'corrupt the morals of youth' in Butler v. State of Michigan (1957). 2- Wepplo: If material has a substantial tendency to deprave or corrupt its readers by inciting lascivious thoughts or arousing lustful desires. (People v. Wepplo). 3- Roth Standard: Whether to the average person applying contemporary community standards, the dominant theme of the material, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest. 4- Roth v. United States 354 U.S. 476 (1957) - overturned by Miller. 5- Roth-Jacobellis: Community standards applicable to an obscenity are national, not local standards. Material is "utterly without redeeming social importance". Jacobellis v. Ohio (1964) - famous quote: I shall not today attempt further to define [hardcore pornography] ...But I know it when I see it. Roth-Jacobellis Memoirs Test: Adds that the material possesses "not a modicum of social value". (A Book Named John Cleland's Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure v. Attorney General of Massachusetts, (1966). 7- Under FCC rules and federal law, radio stations and over-the-air television channels cannot air obscene material at any time and cannot air indecnet material between 6 a.m. and 10 p.m.: Language or material that, in context, depicts or describes, in terms patently offensive as measured by contemporary community standards for the broadcast medium, sexual or excretory organs or activities (indecency is less intense in degree than obscenity).

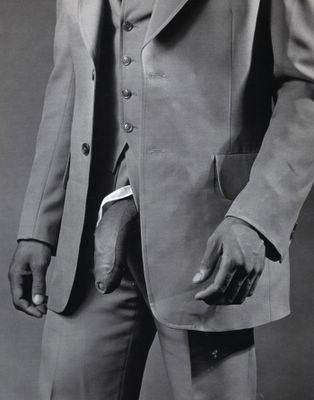

Robert Mapplethorpe's Man in Polyester Suit (1980's). Robert found "god" in a gay bar called Sneakers one drizzly September evening in 1980 after leaving Keller's [a former S& M bar that was now a gathering place for men interested in biracial sex]." Robert saw Milton Moore pacing up and down West Street, and was instantly transfixed by his beautiful face and forlorn stare. Mapplethorpe invited Moore to his apartment. Upon learning of his ambition to become a model, Mapplethorpe agreed to create a portfolio.-- Patricia Morrisoe, "Man in Polyester Suit."

D.H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover (1959 first uncensored edition): "In fact, the most notorious censored works had been books like D.H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover, which contained neither photographs nor depictions of unusual sexual acts. (An obscenity ruling against Radclyffe Hall's lesbian classic, The Well of Loneliness, had made it unavailable to the public until 1948.) In particular, Lady Chatterley's Lover had been 'offensive' because of values that no longer held in society: the once scandalous suggestion of a sexual relationship between a working-class man and a woman of higher status. But attempts to revive the book later met with other objections — the explicit sexual language was considered by some to be unacceptable (particularly if seen by 'your' wife or servants). Nevertheless, it was generally felt that the inclusion of explicit sexual descriptions was not by itself sufficient reason to ban a book that had other literary merit, and this exception was written into the 1959 Act, although that otherwise strengthened the law and made seizures by the police much easier." –Carol Avedon and Lee Kennedy, Nudes and Prudes: Pornography and Censorship.

Gustav Coubert's The Origin of the World (1866). Towards the end of the 1860's, Courbet painted a series of increasingly erotic works, culminating in L'Origin du monde, depicting female genitalia and The Sleepers (1866), featuring two women in bed. While banned from public display, the works only served to increase Coubert's notoriety.-- From Wikipedia on Gustav Coubert

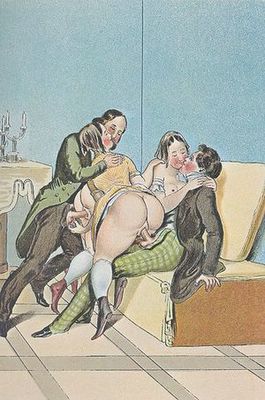

Peter Fendi (1796-1842) Fendi became a respectable artist of the old Viennese school; however, behind his aristocratic mask, Fendi produced some of the crudest erotic imagery of the 19th century. As befits Europe's capital of the skin trade, Amsterdam has two competing sex museums. This one, on Damrak, the divey strip between the station and Dam Square, is the best. Has copies of Indian temple sculpture, pulsating Aubrey Beardsley penises, fun eighteenth-century engravings by Austrian 'orgy artist' Peter Fendi and flickery nineteenth-century films, alongside historical ethno-smut such as ivory dildos and Maori copulation carvings. Opened in 1985, this is the original sex museum. Bizarre touch: a life-size moving sculpture of a flasher. -- A 2000 Dutch travel-agency flyer

Anonymous engravings accompanying the 1797 Dutch edition of Marquis de Sade's The Story of Juliette. The work of the Marquis de Sade, like that of Nietzsche, constitutes the intransigent critique of practical reason... Justine, the virtuous sister, is a martyr for the moral law. Juliette draws the conclusion that the bourgeosie wanted to ignore: she demonizes Catholicism as the most-up-to-date mythology, and with it civilization as a whole...In all of this Juliette is by no means fanatical....her procedures are enlightened and efficient as she goes about her work of sacrilege. Julitte embodies... the pleasures of attacking civilization with its own weapons. She favours system and consequence. She is a proficient manipulator of the organ of rational thought.-- Mark Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightment.

Aubrey Beardsley's Lysistrata (1890's). Even in the last year of his life Beardsley wrote to a friend, "Do you want any erotic drawings?" According to Katherine Lyon Mix in her book A Study in Yellow, "though Beardsley hated evil, he was fascinated by it. A friend declared: 'It was always an enigma to me how and where he acquired all the knowledge of the dark side of life which his work seemed to indicate.'" This is what John Reed has to say about Beardsley's art: "He employed a highly artificial style on subjects that were intensely literary, often of course because they were book illustrations. His designs tease and tantalize, offering no rest for the eye; they often require an illumination of their details before the compositions can be mentally reordered. Living creatures become elements imprisoned within designs that promise no freedom from their empty destinies. Beardsley looked upon the world and found it ugly, but this judgment did not prevent him from converting that ugliness into a painful beauty."--John Reed, The Decadent Style.

François Boucher's Naked Girl (1703-1770). Boucher was a French painter, noted for his pastoral and mythological scenes, whose work embodies the frivolity and sensuousness of the rococo style: "Boucher's patrons lived the lives ordinary people fantasize about: lives of luxury, power, sensual indulgence, elegance, distraction, leisure and wit. What they fantasized about was a distant innocence: the carefree existence of living dolls frolicking with happy animals through feathery groves, by clear waters, under blue silk skies with clouds as soft and white as toy sheep, in sweet landscapes punctuated by the romantic melancholies of classical ruins--picturesque reminders of the transience of worldly power. There is not even much eroticism in these Arcadias, but an almost virginal sensuality: a ballet of indolent flirtation in a setting of curls and flowers. "-- Arthur Danto, On François Boucher, The Nation.

Francisco Goya's Maja Desnuda (1805). In 1813, the Spanish Inquisition confiscated both Goya's Naked and Dressed Maja paintings as "obscene works". He was called before the Inquisition to explain this painting, one of the few nudes in Spanish art at that time. They were confined in San Fernando Academy of Fine Arts for many years and finally entered the Prado in September 1901.

The Western world is obsessed with sex. It is used as a marketing tool, as a weapon in political struggle, as the mainstay of modern journalism and as the daily fodder of soap operas and afternoon shows. In the process, its currency has been debased. Sex has become mechanical — to the point where modern sex education concentrates on biology, contraception, social responsibility and the prevention of disease. In contrast, the ancient instructional tracts discuss the aesthetic aspects of sex, its joys and its delights. The humanist writing of the Renaissance and the erotic memoirs of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries speak of its robust pleasures. Artists and painters have also struggled to depict the human sexual experience. For in sex we are most truly human — at once both animal and god-like.-- Nigel Cawthorne, The Secrets of Love: The Erotic Arts Through the Ages.

Sunday, April 1, 2007

Homework

Thanks for coming to Marina's presentation. I'd like you to write a report of your take of Abramovic's lecture. You could inform your ideas with our discussions of performance art, female art and conceptual art. Bring at least one page (single line, Times Roman 12) for our next class.